AI caught everyone’s attention in 2023 with Large Language Models (LLMs) that can be instructed to perform general tasks, such as translation or coding, just by prompting. This naturally led to an intense focus on models as the primary ingredient in AI application development, with everyone wondering what capabilities new LLMs will bring.

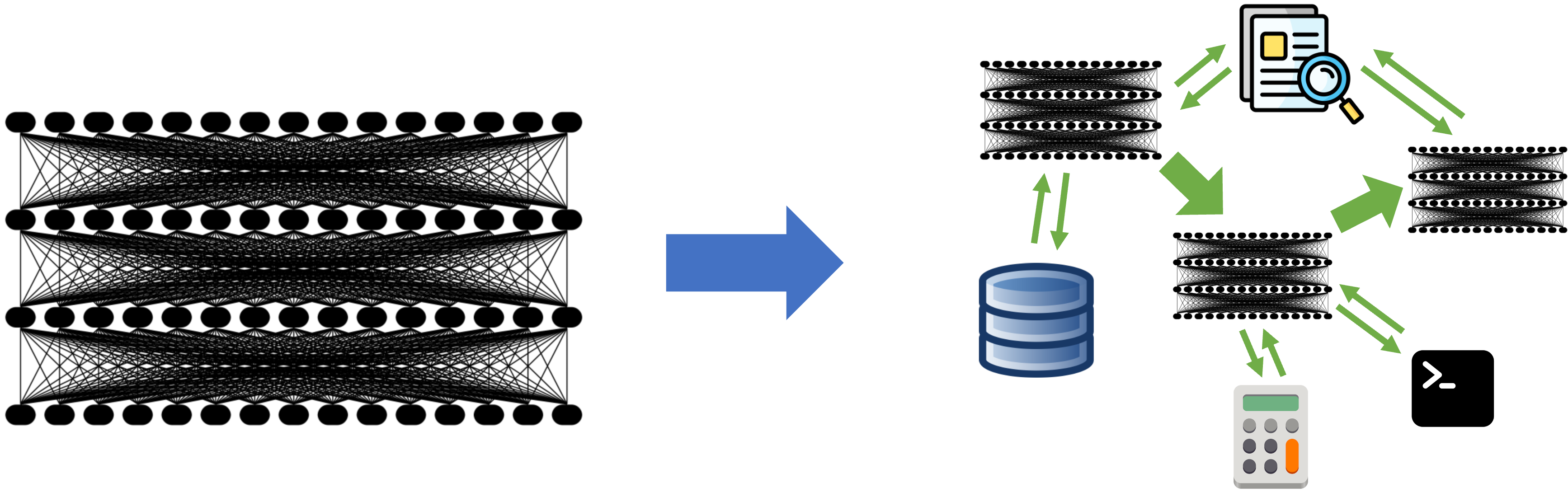

As more developers begin to build using LLMs, however, we believe that this focus is rapidly changing: state-of-the-art AI results are increasingly obtained by compound systems with multiple components, not just monolithic models.

For example, Google’s AlphaCode 2 set state-of-the-art results in programming through a carefully engineered system that uses LLMs to generate up to 1 million possible solutions for a task and then filter down the set. AlphaGeometry, likewise, combines an LLM with a traditional symbolic solver to tackle olympiad problems. In enterprises, our colleagues at Databricks found that 60% of LLM applications use some form of retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), and 30% use multi-step chains.

Even researchers working on traditional language model tasks, who used to report results from a single LLM call, are now reporting results from increasingly complex inference strategies: Microsoft wrote about a chaining strategy that exceeded GPT-4’s accuracy on medical exams by 9%, and Google’s Gemini launch post measured its MMLU benchmark results using a new CoT@32 inference strategy that calls the model 32 times, which raised questions about its comparison to just a single call to GPT-4. This shift to compound systems opens many interesting design questions, but it is also exciting, because it means leading AI results can be achieved through clever engineering, not just scaling up training.

In this post, we analyze the trend toward compound AI systems and what it means for AI developers. Why are developers building compound systems? Is this paradigm here to stay as models improve? And what are the emerging tools for developing and optimizing such systems—an area that has received far less research than model training? We argue that compound AI systems will likely be the best way to maximize AI results in the future, and might be one of the most impactful trends in AI in 2024.

Increasingly many new AI results are from compound systems.

We define a Compound AI System as a system that tackles AI tasks using multiple interacting components, including multiple calls to models, retrievers, or external tools. In contrast, an AI Model is simply a statistical model, e.g., a Transformer that predicts the next token in text.

Our observation is that even though AI models are continually getting better, and there is no clear end in sight to their scaling, more and more state-of-the-art results are obtained using compound systems. Why is that? We have seen several distinct reasons:

- Some tasks are easier to improve via system design. While LLMs appear to follow remarkable scaling laws that predictably yield better results with more compute, in many applications, scaling offers lower returns-vs-cost than building a compound system. For example, suppose that the current best LLM can solve coding contest problems 30% of the time, and tripling its training budget would increase this to 35%; this is still not reliable enough to win a coding contest! In contrast, engineering a system that samples from the model multiple times, tests each sample, etc. might increase performance to 80% with today’s models, as shown in work like AlphaCode. Even more importantly, iterating on a system design is often much faster than waiting for training runs. We believe that in any high-value application, developers will want to use every tool available to maximize AI quality, so they will use system ideas in addition to scaling. We frequently see this with LLM users, where a good LLM creates a compelling but frustratingly unreliable first demo, and engineering teams then go on to systematically raise quality.

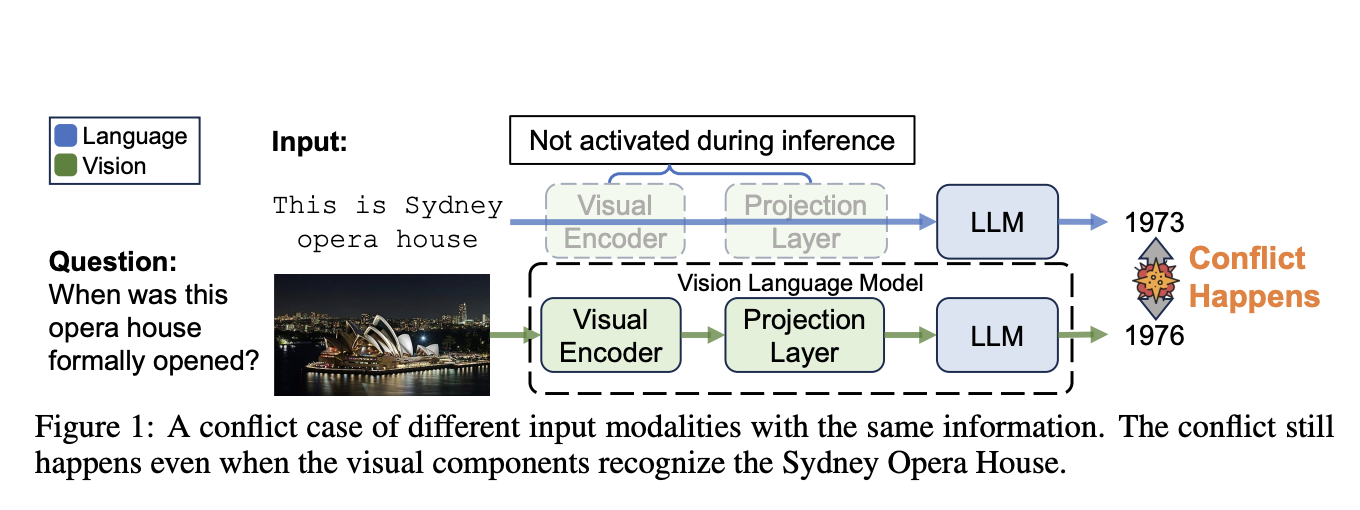

- Systems can be dynamic. Machine learning models are inherently limited because they are trained on static datasets, so their “knowledge” is fixed. Therefore, developers need to combine models with other components, such as search and retrieval, to incorporate timely data. In addition, training lets a model “see” the whole training set, so more complex systems are needed to build AI applications with access controls (e.g., answer a user’s questions based only on files the user has access to).

- Improving control and trust is easier with systems. Neural network models alone are hard to control: while training will influence them, it is nearly impossible to guarantee that a model will avoid certain behaviors. Using an AI system instead of a model can help developers control behavior more tightly, e.g., by filtering model outputs. Likewise, even the best LLMs still hallucinate, but a system combining, say, LLMs with retrieval can increase user trust by providing citations or automatically verifying facts.

- Performance goals vary widely. Each AI model has a fixed quality level and cost, but applications often need to vary these parameters. In some applications, such as inline code suggestions, the best AI models are too expensive, so tools like Github Copilot use carefully tuned smaller models and various search heuristics to provide results. In other applications, even the largest models, like GPT-4, are too cheap! Many users would be willing to pay a few dollars for a correct legal opinion, instead of the few cents it takes to ask GPT-4, but a developer would need to design an AI system to utilize this larger budget.

The shift to compound systems in Generative AI also matches the industry trends in other AI fields, such as self-driving cars: most of the state-of-the-art implementations are systems with multiple specialized components (more discussion here). For these reasons, we believe compound AI systems will remain a leading paradigm even as models improve.

While compound AI systems can offer clear benefits, the art of designing, optimizing, and operating them is still emerging. On the surface, an AI system is a combination of traditional software and AI models, but there are many interesting design questions. For example, should the overall “control logic” be written in traditional code (e.g., Python code that calls an LLM), or should it be driven by an AI model (e.g. LLM agents that call external tools)? Likewise, in a compound system, where should a developer invest resources—for example, in a RAG pipeline, is it better to spend more FLOPS on the retriever or the LLM, or even to call an LLM multiple times? Finally, how can we optimize an AI system with discrete components end-to-end to maximize a metric, the same way we can train a neural network? In this section, we detail a few example AI systems, then discuss these challenges and recent research on them.

The AI System Design Space

Below are few recent compound AI systems to show the breadth of design choices:

| AI System | Components | Design | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaCode 2 |

|

Generates up to 1 million solutions for a coding problem then filters and scores them | Matches 85th percentile of humans on coding contests |

| AlphaGeometry |

|

Iteratively suggests constructions in a geometry problem via LLM and checks deduced facts produced by symbolic engine | Between silver and gold International Math Olympiad medalists on timed test |

| Medprompt |

|

Answers medical questions by searching for similar examples to construct a few-shot prompt, adding model-generated chain-of-thought for each example, and generating and judging up to 11 solutions | Outperforms specialized medical models like Med-PaLM used with simpler prompting strategies |

| Gemini on MMLU |

|

Gemini’s CoT@32 inference strategy for the MMLU benchmark samples 32 chain-of-thought answers from the model, and returns the top choice if enough of them agree, or uses generation without chain-of-thought if not | 90.04% on MMLU, compared to 86.4% for GPT-4 with 5-shot prompting or 83.7% for Gemini with 5-shot prompting |

| ChatGPT Plus |

|

The ChatGPT Plus offering can call tools such as web browsing to answer questions; the LLM determines when and how to call each tool as it responds | Popular consumer AI product with millions of paid subscribers |

|

RAG, ORQA, Bing, Baleen, etc |

|

Combine LLMs with retrieval systems in various ways, e.g., asking an LLM to generate a search query, or directly searching for the current context | Widely used technique in search engines and enterprise apps |

Key Challenges in Compound AI Systems

Compound AI systems pose new challenges in design, optimization and operation compared to AI models.

Design Space

The range of possible system designs for a given task is vast. For example, even in the simple case of retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) with a retriever and language model, there are: (i) many retrieval and language models to choose from, (ii) other techniques to improve retrieval quality, such as query expansion or reranking models, and (iii) techniques to improve the LLM’s generated output (e.g., running another LLM to check that the output relates to the retrieved passages). Developers have to explore this vast space to find a good design.

In addition, developers need to allocate limited resources, like latency and cost budgets, among the system components. For example, if you want to answer RAG questions in 100 milliseconds, should you budget to spend 20 ms on the retriever and 80 on the LLM, or the other way around?

Optimization

Often in ML, maximizing the quality of a compound system requires co-optimizing the components to work well together. For example, consider a simple RAG application where an LLM sees a user question, generates a search query to send to a retriever, and then generates an answer. Ideally, the LLM would be tuned to generate queries that work well for that particular retriever, and the retriever would be tuned to prefer answers that work well for that LLM.

In single model development a la PyTorch, users can easily optimize a model end-to-end because the whole model is differentiable. However, new compound AI systems contain non-differentiable components like search engines or code interpreters, and thus require new methods of optimization. Optimizing these compound AI systems is still a new research area; for example, DSPy offers a general optimizer for pipelines of pretrained LLMs and other components, while others systems, like LaMDA, Toolformer and AlphaGeometry, use tool calls during model training to optimize models for those tools.

Operation

Machine learning operations (MLOps) become more challenging for compound AI systems. For example, while it is easy to track success rates for a traditional ML model like a spam classifier, how should developers track and debug the performance of an LLM agent for the same task, which might use a variable number of “reflection” steps or external API calls to classify a message? We believe that a new generation of MLOps tools will be developed to tackle these problems. Interesting problems include:

- Monitoring: How can developers most efficiently log, analyze, and debug traces from complex AI systems?

- DataOps: Because many AI systems involve data serving components like vector DBs, and their behavior depends on the quality of data served, any focus on operations for these systems should additionally span data pipelines.

- Security: Research has shown that compound AI systems, such as an LLM chatbot with a content filter, can create unforeseen security risks compared to individual models. New tools will be required to secure these systems.

Emerging Paradigms

To tackle the challenges of building compound AI systems, multiple new approaches are arising in the industry and in research. We highlight a few of the most widely used ones and examples from our research on tackling these challenges.

Designing AI Systems: Composition Frameworks and Strategies. Many developers are now using “language model programming” frameworks that let them build applications out of multiple calls to AI models and other components. These include component libraries like LangChain and LlamaIndex that developers call from traditional programs, agent frameworks like AutoGPT and BabyAGI that let an LLM drive the application, and tools for controlling LM outputs, like Guardrails, Outlines, LMQL and SGLang. In parallel, researchers are developing numerous new inference strategies to generate better outputs using calls to models and tools, such as chain-of-thought, self-consistency, WikiChat, RAG and others.

Automatically Optimizing Quality: DSPy. Coming from academia, DSPy is the first framework that aims to optimize a system composed of LLM calls and other tools to maximize a target metric. Users write an application out of calls to LLMs and other tools, and provide a target metric such as accuracy on a validation set, and then DSPy automatically tunes the pipeline by creating prompt instructions, few-shot examples, and other parameter choices for each module to maximize end-to-end performance. The effect is similar to end-to-end optimization of a multi-layer neural network in PyTorch, except that the modules in DSPy are not always differentiable layers. To do that, DSPy leverages the linguistic abilities of LLMs in a clean way: to specify each module, users write a natural language signature, such as user_question -> search_query, where the names of the input and output fields are meaningful, and DSPy automatically turns this into suitable prompts with instructions, few-shot examples, or even weight updates to the underlying language models.

Optimizing Cost: FrugalGPT and AI Gateways. The wide range of AI models and services available makes it challenging to pick the right one for an application. Moreover, different models may perform better on different inputs. FrugalGPT is a framework to automatically route inputs to different AI model cascades to maximize quality subject to a target budget. Based on a small set of examples, it learns a routing strategy that can outperform the best LLM services by up to 4% at the same cost, or reduce cost by up to 90% while matching their quality. FrugalGPT is an example of a broader emerging concept of AI gateways or routers, implemented in software like Databricks AI Gateway, OpenRouter, and Martian, to optimize the performance of each component of an AI application. These systems work even better when an AI task is broken into smaller modular steps in a compound system, and the gateway can optimize routing separately for each step.

Operation: LLMOps and DataOps. AI applications have always required careful monitoring of both model outputs and data pipelines to run reliably. With compound AI systems, however, the behavior of the system on each input can be considerably more complex, so it is important to track all the steps taken by the application and intermediate outputs. Software like LangSmith, Phoenix Traces, and Databricks Inference Tables can track, visualize and evaluate these outputs at a fine granularity, in some cases also correlating them with data pipeline quality and downstream metrics. In the research world, DSPy Assertions seeks to leverage feedback from monitoring checks directly in AI systems to improve outputs, and AI-based quality evaluation methods like MT-Bench, FAVA and ARES aim to automate quality monitoring.

Generative AI has excited every developer by unlocking a wide range of capabilities through natural language prompting. As developers aim to move beyond demos and maximize the quality of their AI applications, however, they are increasingly turning to compound AI systems as a natural way to control and enhance the capabilities of LLMs. Figuring out the best practices for developing compound AI systems is still an open question, but there are already exciting approaches to aid with design, end-to-end optimization, and operation. We believe that compound AI systems will remain the best way to maximize the quality and reliability of AI applications going forward, and may be one of the most important trends in AI in 2024.